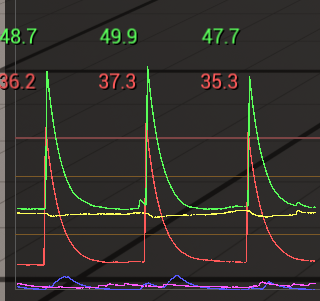

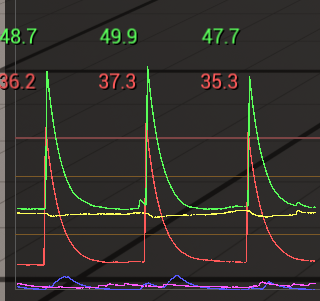

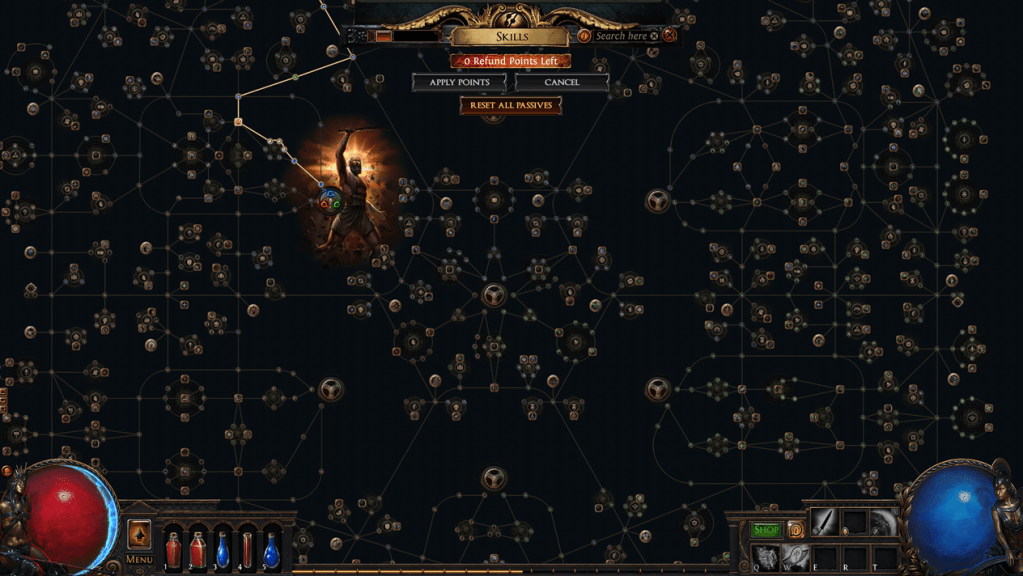

One of the few things programmers can agree on is probably that a frame time graph shouldn’t look like this:

Numerous, extremely strong spikes that are not only noticeable but so severe that they might directly affect gameplay can ruin the feel of a game no matter how high the average framerate is. The interesting thing about this (slightly exaggerated) example is, that even without actually profiling the game, many programmers will be able to identify the reason behind this behavior based on the graph alone: Garbage collection

Garbage Collection (GC for short) is a very basic feature that is present not only in many Game Engines like Unreal and Unity, but even some programming languages like C# come with it built in. It’s a common solution to one of the basic problems of any program, memory management.

Basically, every time you create an object in a program, it needs to go somewhere in memory, consuming a part of your precious RAM. When working in a given framework/engine, you rarely need to think about this step, it will automatically figure out how many bytes the object needs and ask the OS to reserve the needed space. So far, life is simple.

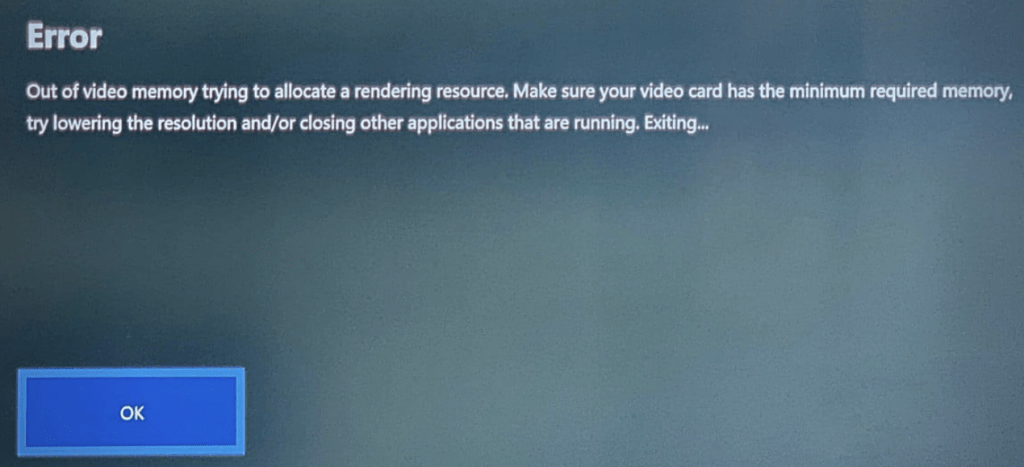

It gets more complicated as your game runs. Most of the objects and data that are loaded in a game aren’t meant to stay there forever. Menus are closed, levels are changed, etc. Even after a little while most of the data might not be needed anymore, while at the same time, our game can’t stop loading and spawning new stuff. In most cases, the RAM will just fill up. What happens then depends on the platform, but let’s just say that it’s a bad thing:

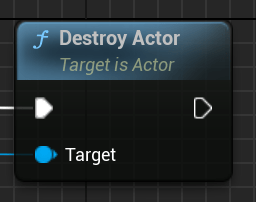

Described like that, the solution might seem easy – everything that is spawned/loaded needs to be destroyed again later. This seems quite straightforward – most of the time we do this anyway, right?

Well, actually we don’t. Most of the objects that Unreal spawns aren’t explicitly spawned actors, but all kinds of resources and helper objects that we don’t even think about when talking about gameplay code. Just spawning a single cube in Unreal doesn’t just spawn a single actor, but a bunch of subobjects – a mesh component, a material, texture objects, the mesh asset, etc. etc.

How many things are actually loaded might vary – lot of data might be already available in the RAM and doesn’t need to be loaded again. If you spawn 10000 cubes with the same metal texture, the metal texture will be loaded only when spawning the first one. The following 9999 can luckily reuse it.

Figuring out when data actually needs to be loaded is easy – Unreal manages an internal list of all active objects.

But what happens when you destroy one of the cubes? Do you unload all the resources associated with it, like this grey texture? You could do this, but now all the other cubes lost their textures.

The main issue is, that objects can be used and referenced by multiple sources, and figuring out when a piece of memory isn’t needed anymore is complicated. If this isn’t done 100% correctly, it can happen that data that isn’t needed anymore is left behind, piling up over time, without a way of clearing it. This is called a memory leak and one of the main reasons why C++ (a language that was built for manual memory management) fell out of favor for the development of most applications (besides games and other low-level software). We could of course ask all the objects in our game if they still need a given piece of memory, every time anything gets destroyed but that would take a lot of time and destroy performance. Or the code would need to manage all added and removed references manually – an error-prone approach and even a single memory can fill any remaining RAM if given enough time.

Garbage Collection promises to offer a solution to this problem by – get ready – regularly asking all the objects in our game if they still need all the objects in the game and then destroying/unloading the ones that are not needed anymore.

Wait, this can’t be right, right? Wasn’t this approach deemed way too slow? Well, the deciding difference is, that Garbage collection isn’t run all the time. It’s run sometimes mostly in regular intervals. So it’s still extremely slow, but at least it’s only sometimes really slow. Hence this beautiful frame graph:

This is also the reason, why many developers are not particularly fond of Garbage collection, there are enough talks and articles out there that call it outright unusable for real-time software. Just listen to the passive-aggressive jabs at it in this talk about Call of Duty’s UI optimization:

Despite this, it’s basically the standard solution used by all the off-the-shelf engines like Unreal or Unity. Simply because Garbage Collection is ‘good enough’™ ‘most of the time’™. It’s probably good enough if

- Your game doesn’t have a lot of objects

- Your game isn’t too dependent on a locked framerate

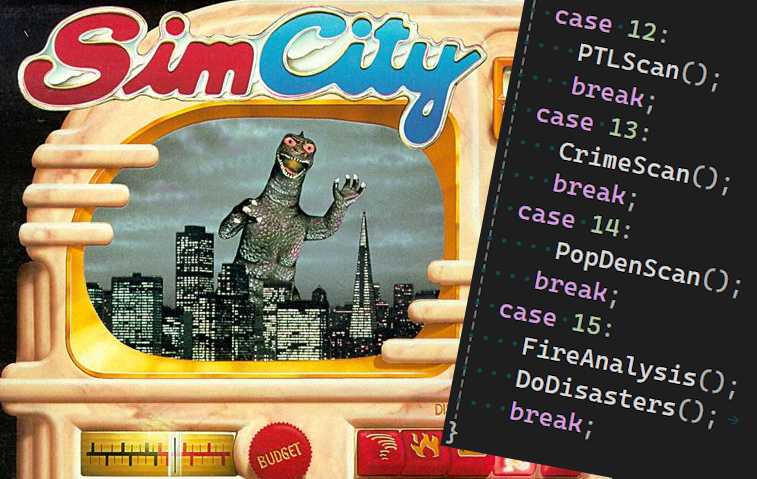

The more objects your game state consists of the more stuff the garbage collection needs to scan, therefore taking longer. So when working on a simple walking simulator you might not even notice the GC doing its work, but when working on a large-scale strategy game, those spikes might escalate in literal freezes that can take multiple seconds!

Couldn’t we just use fewer objects?

Since the time needed for a full GC run scales with the number of objects to scan, reducing the number of objects is probably the closest thing to solving the problem at its root. The obvious drawback is that you have to make big architectural changes for very slight gains. Only do this if GC is a big problem in your project and you have an easy win in mind to reduce the number of objects by a meaningful amount with a very low risk of breaking stuff. Every amount with 4 digits is probably not meaningful.

Small steps: Tweaking the frequency

The first (and simplest) thing you can do is to just tweak the interval of the automatic GC runs in the project settings:

Less GC runs equals fewer frame spikes. There are two main drawbacks: For once, the actual frame time spike might be even higher than before since more objects need to be destroyed if the clean-up is done less often. Luckily, actually destroying the objects is only part of the spike, so doubling the interval will not directly double the spike duration.

The other drawback is that unneeded objects will be kept around for longer, therefore increasing the RAM usage of your game. Depending on the target platform and the game, this might not be a big issue.

Calling the GC manually

A long frame in itself doesn’t have to be that bad, it becomes bad by the player experiencing the long frame. A long frame that happens while lining up a perfect headshot can singlehandedly ruin a whole play session. The same spike while waiting for a door animation to finish will barely register and a spike hidden in a loading screen becomes completely invisible.

Opening any full-screen UI will basically force the player to take a moment to parse the new information before they will do any new inputs again.

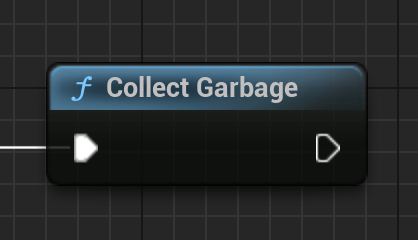

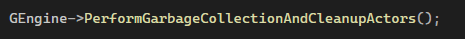

We can use this opportunity to simply call the GC manually, whether in Blueprints or C++.

The great thing about such manually called GC runs is, that every time it is called it will reset Unreal’s regular GC interval back to 0. If we have enough spots for “invisible” GC runs, we won’t ever see any visible frame spike (except in the profiler).

Sidenote: Unreal actually does this already. Every time a level change happens, the Engine will also call the GC, which due to the game stalling anyway while loading the level goes basically unnoticed.

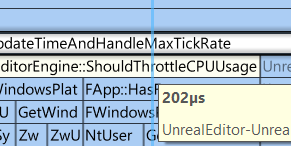

Getting ambitious: Don’t do regular Garbage collection at all

Sadly there won’t be always enough opportunities for invisible GC runs, at least not without increasing the regular GC interval to quite absurd lengths. But what if we did? What stops us from increasing the regular interval to a value so high that it will basically never happen? In many games, this might be somehow feasible, but there is always a remaining risk with this option that if the player avoids all points of manual GC runs, they could still provoke the game to run out of memory. It might happen very rarely, but we can’t take this risk, right? Well, we can use an almost hidden feature of Unreal to safeguard this approach. Further above we already tweaked the interval of garbage collection to at least reduce the number of GC spikes. But what the Unreal Interface (and its documentation) doesn’t tell you is, that we can not only set one interval but two different ones: A default one that can be set simply in the project settings screen and a second one not visible in the project settings window, that is only used in low memory scenarios. To change it just add a line in DefaultEngine.ini under:

[/Script/Engine.GarbageCollectionSettings]

gc.LowMemory.TimeBetweenPurgingPendingKillObjects=30

gc.LowMemory.MemoryThresholdMB=2048This value is meant to increase the frequency of GC when we are in danger of running out of memory.

By setting the regular GC collection to an extremely high value we can basically block regular (noticeable) GC runs, instead relying on manual runs at certain points of gameplay. The LowMemory-Interval will serve as a fallback solution in the unlucky case that the mentioned points of manual GC runs are not enough.

The main drawback is that the game will probably use much more memory on average since it will only start to free up memory after the set limit is reached. This is bad in theory, users don’t like wasteful software, just ask any user of Google Chrome. But games (especially on console) are in general free to use (almost) all available memory as long as it helps to avoid stuttering – nobody who doesn’t check the task manager will even take note of this. Never be scared to waste resources to improve the game experience 😉

Leave a reply to Lars Thießen Cancel reply