Most of the time, when a game struggles to reach a certain framerate, the problem lies in its visuals. All the fancy rendering features that modern engines offer these days, such as Global Illumination, Subsurface Scattering and so on, can easily overwhelm any gaming machine, no matter how much money you have spent on it. In general, this problem is easy to fix – just turn off or turn down all those fancy settings until the framerate climbs back over the magic 60fps line (or 120, or whatever line you decided your game should be able to climb).

But at some point – which will come earlier or later in some game genres something strange starts to happen: No matter how low the resolution is pushed, no matter how little effects are on the screen – the framerate just isn’t changing anymore. If this happens congratulations – you are not bottlenecked by the graphics anymore, but by the CPU. Either the execution of the gameplay code or the preparation of the scene before being rendered on the GPU takes more time than the rendering itself. Especially the former case isn’t straightforward to optimize. There is no simple setting to turn down and there is no way we could process the gameplay with some form of ‘lower quality’. We can’t just skip the processing of weapon effects because a frame takes too long, most game designers expect their gameplay to be actually executed as designed (quotation needed).

The process of optimizing code for performance is a vast field in itself and there is a whole library of knowledge available to dig into. You might stumble into long discussions about arcane technologies like byte-alignments, mutexes and cachelines. If you think you might enjoy such deep dives (I know I do) go for it. But in most cases, those arcane detail optimizations are neither useful or recommendable.

Try to move the goalposts

If you are like me, you might enjoy optimising code. Saving milliseconds and writing clever caching algorithms can be a fun hobby. But even if you do, that’s not your goal as a game programmer. Every minute spent on optimising code is a minute lost on implementing flashy new features – and flashy new features are one of the main things players want from a game 😉

Changing the game design to avoid a technical challenge is always faster than solving the challenge. Of course, programmers shouldn’t completely rewrite game design documents just to reduce their own workload, but in surprisingly many cases, even small design changes can lead to much better performance, simply because game designers don’t have much visibility when it comes to the technical ramifications of their work.

A simple example could be a short sentence such as “The enemy AI constantly evaluates all possible targets”. Most programmers would interpret the word “constantly” to mean “every frame”. But what are the chances that the game designer who wrote the sentence actually meant that specific frequency? In “normal English”™, “constantly” is a surprisingly vague term. In reality, what the game designer meant was that enemies would react to changes in available targets within a reasonable amount of time. A small difference from the player’s point of view, but one that can actually save an order of magnitude in computation – and therefore a few dozen hours of work.

Always ask your game designer what is really needed from an implementation – and what is not.

Don’t start optimizing before profiling

Assuming that, despite all the shaking around, the goal posts have not been moved, we still can’t start optimising the game, simply because we don’t know yet, which part of the game is responsible for the low framerate. Often it might seem obvious what part of your code is particularly slow. Some features like pathfinding, AI or simulations are the first suspects if the framerate drops. Or this one 1000-line function you wrote last week? Of course, it has to be the culprit. But those guesses are after all just guesses, and no matter your experience, guessing the performance of a piece of code is hard. Most games consist of a lot of pieces of code (quotation needed), most of them probably not even written by you or even hidden away in some handy library that you didn’t even know existed. So before spending even a minute optimizing anything, you have to profile your code.

When it comes to profiling there are roughly two methods available. The first one is to add custom code to your functions that measures the time spent in these functions. The Unreal Engine for example offers custom-made macros for doing so and can even visualize the data collected this way in its custom tools (Unreal Insights). This way of profiling returns very precise results, often using the most precise clock offered by the OS.

The other method is using a sample-based profiler that will check in regular intervals which function(s) a given program is executing right now so it can estimate how much time was spent on those functions. The biggest drawback is that the profiler wont necessarily catch all calls to a function. If for example a function is called and finished between two samples this function wont be visible in the profiler and the interval will be added to the function that was called before or after the interval instead. In my experience, this lack of precision is mostly outweighed by the fact that a sample profiler will measure the impact of any function, without you marking it beforehand. This is a huge help since, as mentioned, guessing which parts of your code are slow is hard and many of your guesses will be wrong. One sample-based profiler that I often recommend is Superluminal, but there is a wide range available.

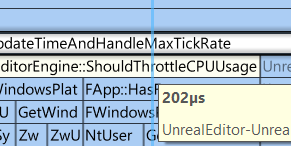

Reading the profiling data

Most profilers will return some form of hierarchical list showing the time spent in each function:

This seems all fine and good, but what are we supposed to do with this knowledge? Do we just search for the slowest function and optimize that one? In most cases, this wouldn’t even be a bad start, but what we are actually looking for are not the current timings of our functions but functions with the highest optimization potential. This means we not only need to know how long a function is running, we also need to guess how long it should be running if optimized. This might sound like a very unscientific approach, especially after spending time gathering all those precise-looking numbers. And for the most part, it actually is, but especially when just starting to work on a rather unoptimized game, there are some easy wins to have.

Let’s make up some simple examples. You are developing an RPG with a lot of NPCs and after profiling a busy city scene you have three functions on top of your profiling results:

- HandleNPCNavigation 7.2ms

- UpdateHealthBar 4.1ms

- UpdateManaBar 0.1ms

Which function would we start to look into first? Clearly, HandleNPCNavigation is the slowest function, but we probably expect the navigation of multiple NPCs to take a good amount of time , no matter how much we optimize it. Maybe we could make it twice as fast, saving 3.6ms. But this already seems very optimistic. On the second place in the list, we have the function ‘UpdateHealthBar’, which takes significantly less time. But in this case, it’s safe to assume that a correctly implemented health bar update should probably take far less time, probably even close to zero. We even have some data to base this estimate on, since UpdateManaBar which sounds like it should do something similar takes close to zero milliseconds. So ‘UpdateHealthBar’ has an optimization potential of ~4ms, we should look into that one first, followed by ‘HandleNPCNavigation’ which has a potential of 3.6ms. ‘UpdateManaBar’ remains uninteresting, since even if we’d make it a magnitude faster we couldn’t save more than 0.1ms.

Start at the top

So we have a list of potential candidates to optimize, now what?

When you just google “how to make code go fast” most of the tips and techniques you will find will be focused on advanced low-level optimization. Stuff like “How to save a position in 7 bits”, “How to save assembly instructions”, “Let’s beat the compiler at its own game” etc. While all those methods are indeed effective, you should avoid using them for as long as possible. If a game has performance problems it’s rarely due to a function unnecessarily copying two bytes more than expected, but rather some architectural flaw on a higher level. In general, you want to pull the biggest lever available to you. Or to give a more concrete example: If your pathfinder handles 10000 requests per frame, making the single request go slightly faster won’t help much, finding out why you have 10000 requests in the first place will.

Do less

Computers are crazy fast nowadays (quotation needed), so doing a single thing very slowly is basically impossible. Most of the time, if something takes time it does so because we do it a lot of times.

Let’s look at some pseudocode:

foreach (NPC* npc in NPCList)

{

npc->DoStuff();

}In such a case there a two things we can do: First, we could try to make the stuff that is done faster. If we manage to make ‘DoStuff’ twice as fast the whole example code will be executed twice as fast. The other approach would be to do the stuff less often. Maybe not all NPCs need to do their stuff all the time? Maybe we can narrow it down to a subset of NPCs that actually need to do stuff? If we can narrow down the list to half the size, the whole example would be twice as fast as well.

But without further context, it’s impossible to know which of the two approaches has more potential time saving, right? Well on a theoretical level this would be correct, but in practice trying to shrink down the list is more often the better approach than not. Mainly because filtering a list based on certain criteria has the potential to completely annihilate the list – in a best-case scenario no work needs to be done at all. Making meaningful optimizations on an arbitrary function is much harder in comparison and we already know that even in a best case the function will still take some time.

Avoid Quadratic Work Loads

Assuming that the cleverly named function ‘DoStuff’ from the previous example always does the same work, this scenario scales (almost) perfectly with the amount of data we were processing – twice the number of NPCs results in twice the time the loop took. In computer science algorithms with this characteristic are described as algorithms with the complexity O(n), meaning the time they take will scale with the number of elements n to process. This characteristic makes them quite easy to reason with. ‘Twice the amount of data -> twice the amount of time spent’ is an intuitive mindset. Sadly some algorithms don’t behave that nicely. Next on the list would be algorithms with an exponential complexity O(n²). This means that the spent time scales to the quadrat of the number of processed elements. To fit our example of our NPC list let’s see what such a function could look like.

foreach (NPC* npcA in NPCList)

{

foreach (NPC* npcB in NPCList)

{

npcA->UpdateSightlineToOtherNPC(npcB);

}

}This function doesn’t take twice as long just because we increase the number of NPCs from one to two, but four times as long, since its inner function call is executed n x n times. Sounds slow, right? To make matters worse, it makes estimating the duration of a call really unintuitive. Let’s imagine we have a level with 10 NPCs and every frame we are updating the sightlines of our NPCs. How much slower would this function be if a level designer increases the number of NPCs from 10 to 12? It’s a rather small change, but the result would be that the function almost takes 50% more time to call! This makes those algorithms especially tricky. You don’t notice how slow they are until somewhere, somehow the number of elements is increased by a good amount, and suddenly, everything stutters.

In the example, the quadratic nature of the code is very easy to spot. Most programmers will instinctively raise an eyebrow every time they see a loop inside another loop anyway. But often those quadratic algorithms are harder to spot. Let’s split up the example into two functions:

void UpdateAllSightLines()

{

foreach (NPC* npc in NPCList)

{

npc->UpdateSightlinesOfNPC();

}

}

void UpdateSightlinesOfNPC()

{

foreach (NPC* otherNPC in NPCList)

{

UpdateSightlineToOtherNPC(npcB);

}

}

Both functions individually seem to have linear complexity, since they use simple loops, you have to be aware of their relation to each other to spot the issue.

There is no general optimization for quadratic algorithms, but they are a good reason to:

1. always use worst cases scenarios during profiling

2. introduce hard limits for elements that are potentially used by an quadratic algorithm.

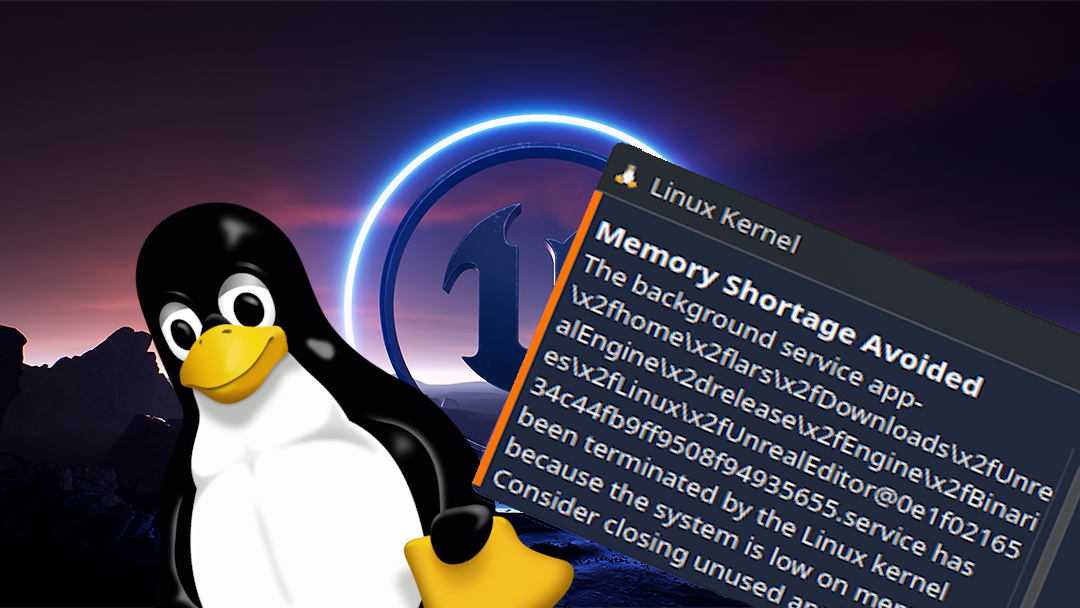

If your code isn’t the problem

More often than not, most of the time spent in a single frame won’t be spent inside your gamecode but deep inside the engine/framework you are using. This might feel like a win at first: Hey, it’s not my fault that the game is running so badly. The engine is just too slow for my great game.

Well, maybe this is actually the case (hint: most of the time it’s not), but in the end the performance of your game is still your responsibility. So no matter the reason, how do optimize those cases?

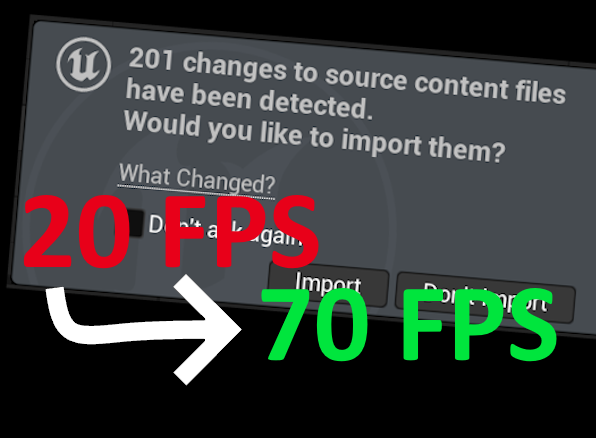

Solution 1: Change your usage

As mentioned above, most engines out there are already well optimised. If for some reason the engine takes an unreasonable amount of time to do something, it’s probably not meant to be used in the way you’re using it, but that doesn’t mean the engine can’t do what you need it to do in general. The tricky part is figuring out the intended way of doing things. A good example of this is the Unreal Engine’s actor system. To quote Unreal’s own documentation: “An actor is any object that can be placed in a level. So far, so simple. So what would you do if you needed a small swarm of insects crawling across the ground?

If your answer was “spawn 10,000 actors”, you are in for a nasty surprise, because Unreal implicitly expects you to keep the number of moving actors in a certain range – definitely below 10,000. All the code for handling and rendering that many actors will break under that load. This doesn’t mean you can’t have your crawling vermin. It just means that you have to use a different system of the engine that was built for those requirements. In this case, for example, Unreal’s Niagara particle system would be a much better approach.

This example was easy, especially since Epic Game themselves used this very scenario to demonstrate their new system.

But finding the right (or at least the wrong) approach can be much more complicated, especially if the engine or framework was not designed with your exact use case in mind.

Just replace our hypothetical swarm of identical insects with an army of distinctive fantasy creatures of varying sizes and you may need to find a new approach – or bend the existing one further than you would like.

Solution 2: Roll your own solution

If all the available systems can’t handle your specific workload, your last resort may be to write your own. But be sure that you have exhausted all available options before taking this step. As mentioned above, it’s safe to assume that most engines out there are already well optimised. Spending time trying to beat a battle-tested system like PhysX is (in most cases) not a good use of your time (unless you have a lot of time and money – or you’re really smart).

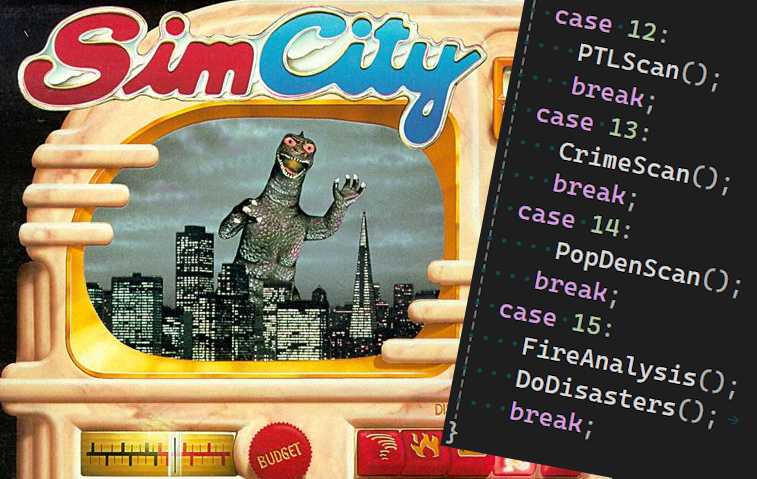

But there are exceptions. Most engines and frameworks are designed to be as generic as possible to support all kinds of use cases. For example, a pathfinder that is part of an engine like Unity or Unreal has to potentially work in a wide range of scenarios, including applications outside the games industry. It has to support open world games as well as small confined spaces, static levels as well as dynamically changing ones, etc. etc.

You may not be able to write a faster or better general pathfinder – but you may be able to write a faster pathfinder for your game. For example, if you are working on a grid-based city builder, simply using that grid for pathfinding will always be faster than the generic navmesh solution provided by Unreal. It might break sometime in the future when you decide to mix the city builder with an online VR-MOBA-RPG-Open-World-Adventure – but that should be the least of your problems.

Leave a comment