Of course, anyone who programs is a programmer by definition. But after teaching programming to game development students for four years, I know that there are a lot of students who wouldn’t dream of calling themselves programmers – they just started programming because, well, someone has to. Because there always comes a point when a big pitch document isn’t enough anymore, when you want to test and experience your idea inside an engine. They open up their editor with a few overwhelmed memories from their last programming lecture and… hit a wall. Nothing works, everything crashes, and why does nothing work like the tutorial they saw on youtube shorts last night?

So are there any strategies to just get things done? Even without deep programming knowledge? Of course there are, and luckily you came to the right place.

Tip 1: Defend your headspace

Do you know how the code you’ve written so far works, exactly? If your program is longer than four functions, probably not. The mental headspace needed to model even a simple program is way too big as that even experienced programmers could actually do it? The solution? Don’t use your headspace, use pen & paper. You can’t remember in which order a number of functions are called in? Just give up remembering it and write it down instead. This is not an exam, cheat sheets are not even allowed but encouraged. Most programmers have a notebook sitting at their desk at all times exactly because they can’t remember any sentence longer than three words. If you see a programmer without a notebook, it’s just because they prefer a virtual notebook at their screen.

Have you seen the movie “A Beautiful Mind”? In this film, the main character, a math genius named John Nash works on his theorems by covering the windows of his dorm room with formulas, numbers and scribbles. The scene illustrates two important facts about John Nash:

- He is very smart

- He can’t remember stuff

If the inventor of the Nash Theorem can’t remember numbers, you don’t have to 🙂

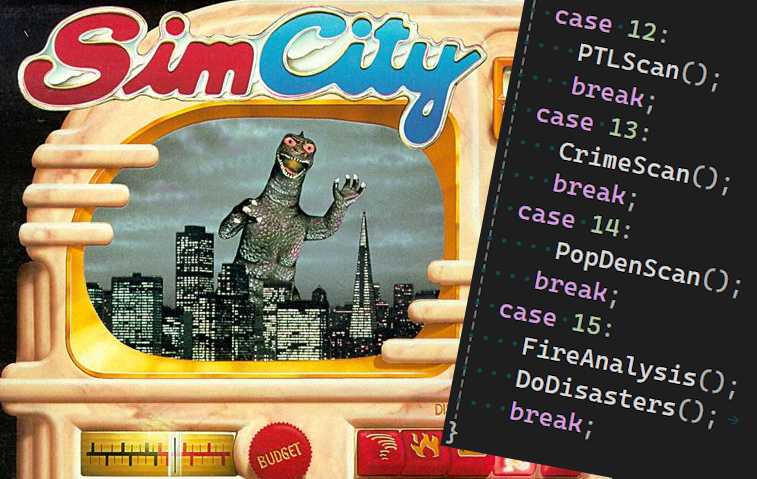

Tip 2: Google on the correct problem layer

Googling errors is an art, but even without mastering it, there are some common pitfalls that you can avoid. The most common mistake I see when students use google to look for solutions is that they are changing the problem layer. What do I mean by that? Let’s assume you are working on inventory feature, something like Stardew Valley:

In this case the concept of programming the inventory is the top layer of your work. Right under it comes the implementation layer, the actual code that is supposed to make the inventory work. Most likely it consists of some container like an array or a map/dictionary to hold the items and some functions to add or remove items. And at some point you notice that a function that you are using to modify this container doesn’t behave as expected, maybe the number of items in the inventory is always off by one or accessing an item with a certain index is returning the wrong item.

After some trying around and not finding the issue you decide to ask Google for help. What are you googling for? I’ve seen a lot of cases where students would think to themselves:

“I’m working on an inventory in Unreal engine, so let’s google for ‘Unreal engine inventory error’”.

This of course lead them to some general tutorials how an inventory could be implemented in Unreal, sometimes similar to their solution, sometimes completely different. In the best case they would try to apply parts of the tutorial to their implementation, notice that it didn’t apply and give up. In the worst case, they would throw their whole implementation away and start over, re-implementing a whole new inventory system.

Both cases can be avoided by staying on the problem layer. If the issue is that a specific function isn’t doing what you think it should be doing, google this function, not the context you are using the function in.

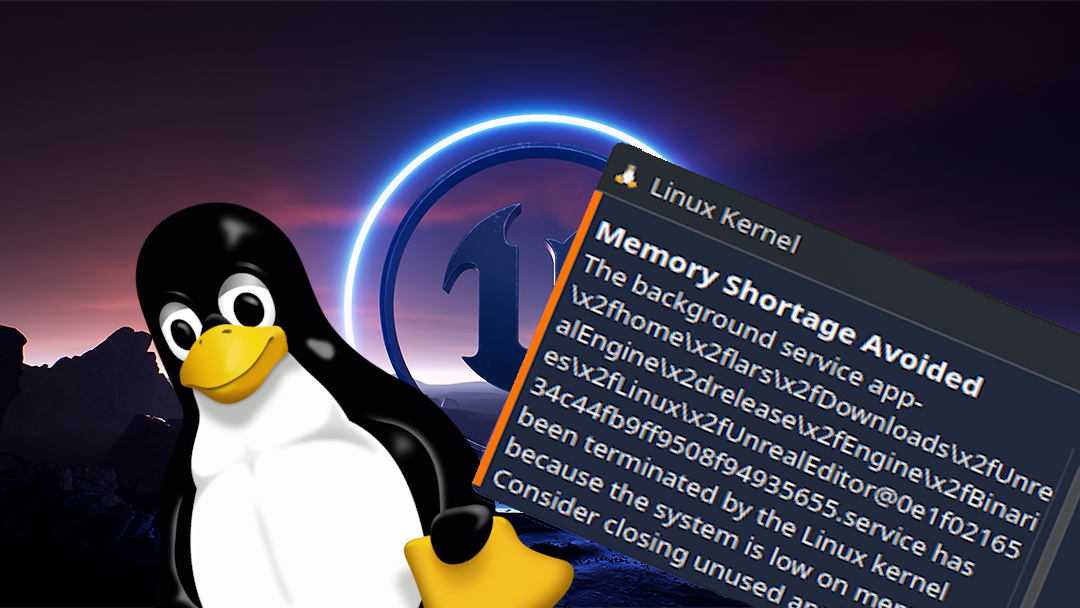

Tip 3: Error messages are your friend

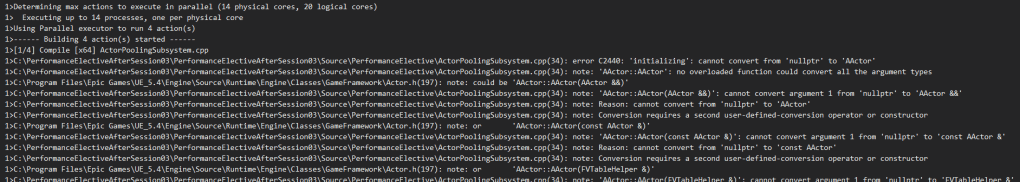

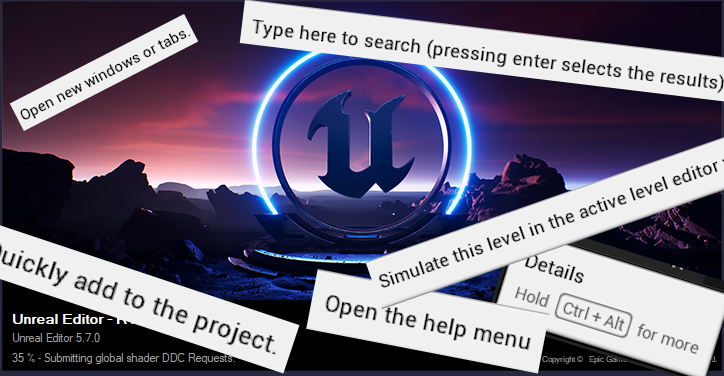

After reading through a bunch of tutorials and setting up the project you are all set for a productive afternoon of programming. You write a single line, press the compile-button and …a list of 342 cryptic error messages pops up. Seems like programming isn’t meant for you and you have 342 pieces of evidence for that, right?

To get the most important fact out of the way first: Even the most genius programmer in the world won’t be able to avoid seeing error messages. Most likely they will even trigger more error messages than you, because they don’t try to avoid them as actively. For them, error messages are not a sign of a personal error they made but a helpful pointer to an error in the code.

Maybe this negative connotation comes from other “normal” error messages. If an error message is shown while trying to do video call and tells me that my webcam isn’t working I am also annoyed and frustrated. It’s not my job to get webcams working, my job is (at least partially) to do video calls.

When seeing an error message while programming, I don’t feel this frustation, since the whole concept programming is about solving errors. If there wouldn’t be an error, I wouldn’t need to program (and wouldn’t have a job).

The real horror starts if there is no error message, anyways.

Tip 4: You don’t need three dimensions

This one is a very specific gamedev problem to have: Thinking in three dimensions.

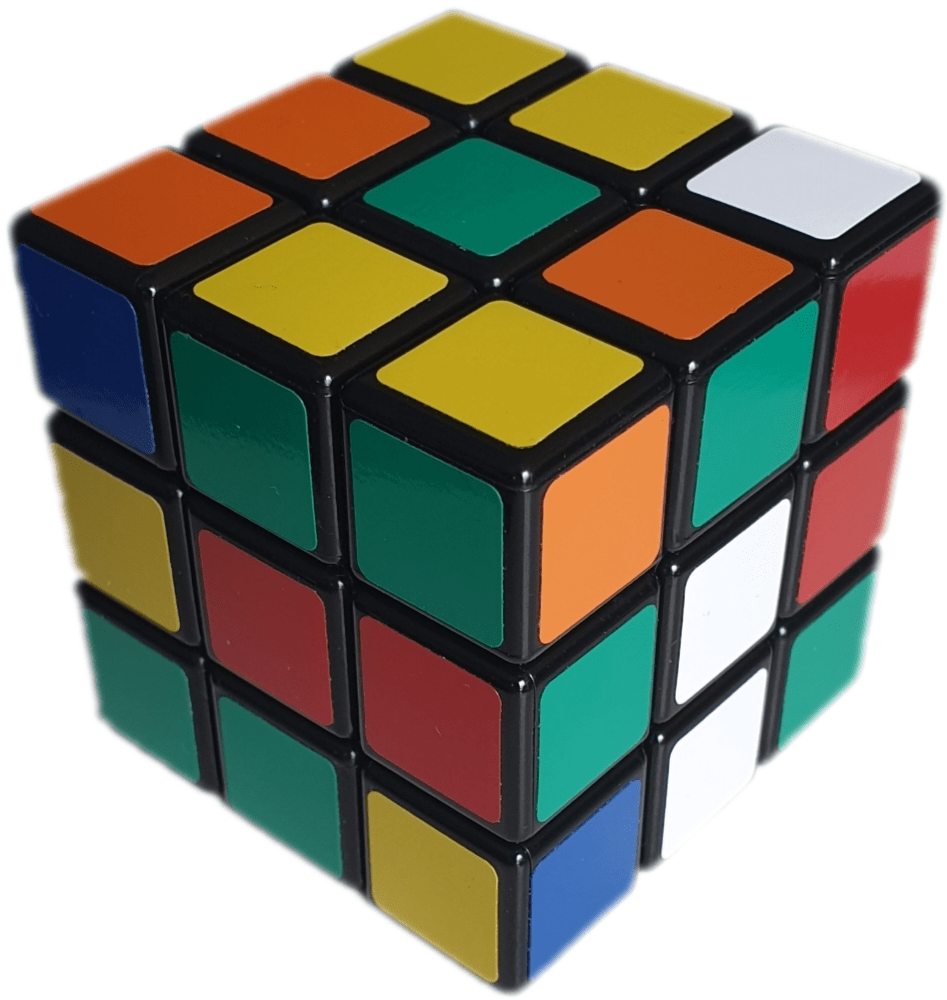

Most people are not good at it. Just look at this picture of a rubic’s cube and try to rotate it in your mind:

Can you do it? If yes, bravo, you have a higher spatial intelligence than me. The rest of us is better off trying to think in two dimensions instead.

Luckily, most three dimensional problems and algorithms also work fine in two dimensions. As long as you can imagine and implement an operation in two dimensions, you can almost always also implement it in three dimensions. And you can even use pen and paper now to visualize it instead of trying to rotate imaginary point.

Tip 5: Plugins save time, but not (all) complexity

“Do I even need to code this stuff? Isn’t there plugin/addon/asset pack for this?”

Since Unity introduced it’s asset store in 2010, buying and using existing technology from other developers became a lot easier and more commonplace. Why program a settings menu yourself if you can just use a ready-made from the store?

And indeed, there are many good reasons to use plugins, not only to save coding time. In many cases plugins will have a lot more mature code than the DIY-solution that you might create yourself. In other cases the implemented technology is so complex that implementing it yourself might not even a valid option in the first place. Nvidias’s DLSS plugin is a good example for that, no developer would even think of implementing this themselves.

At the same time nothing is easier than to underestimate the effort needed to use a piece of already written code and to connect it to the rest of a game.

The main trap is the expectation that using a plugin for a given feature makes this feature “free”. If you don’t have to develop it yourself, this has to mean that the development effort of the feature is zero, right?

Hm, for a while this might even hold true, ignoring that most of the time you will probably need to spend at least a little bit of time on getting it to work. But over short or long, any “free” feature will require some extra work. Maybe because the inventory system you integrated has to be connected to your savegame system. Or because the default input bindings of the fancy parkour plugin conflict with your cool couch coop mode. In any case, at some point you will have to dive into the thing that you downloaded. Maybe just on a shallow level, maybe down to the deepest core of it. And you’ll have to think how this foreign stuff of code works in your game, and if it even works in your game. This isn’t a problem in itself – the same would be true for the code that you would have written. But remember, you might have put this code into your game as if it was “free”, so it might not be the one small feature that you would have implemented, but mountains off secondary features, convinience stuff and abstraction layers. There is a real risk of amounting mountains of a very specific tech debt before your own codebase even started to take shape.

Don’t get me wrong, you should plugins where needed – just don’t stop considering the connected scope and effort like you would do when coding it in-house.

Tip 6: Never throw away your own code

Do you know what the best code in the world is? It’s the code you can understand.

Do you know whose code is the easiest for you to understand? It’s all the code you used to write yourself, code you had to understand at least once before.

And there you have it: Bravo, you write the best code in the world. So treasure it, don’t let it rot on old hard drives or some forgotten Dropbox account. Build and nurture your personal codebase – it will come in handy at some point, even if it takes a while. There will be points in your coding where you remember solving a particular problem in the past – it would be a shame not to be able to reuse that finished work. Maybe you can reuse a clever trick you figured out on a previous project. Other times, it’s just a good place to look up examples of how to write certain syntax. For example, I could never remember the syntax of a timer delegate in Unreal, so I always copy and modify an existing one. It’s faster than searching the official documentation and it saves headspace (see tip 1 above).

Tip 7: The verb-object-method

The most blocking issue is often the programmer pendant to writer’s block: You have a game design, but no idea where you should even start translating it into code. You might read a line about a gun hitting an enemy and making damage and you vaguely remember that you need a linetrace to do that, but where and when should this linetrace be executed?

The best thing you can do in this case is to start with a list of the classes and functions you’ll need to implement the feature. How do you know which ones are needed? In most cases just listing all nouns and verbs in your game design is already enough. Simply create an empty class for every noun, and an empty function inside those classes for every verb. Let’s try an example: Suppose you have a sentence like:

“The player can shoot enemies with a gun to damage them.”

Using the simple noun-verb method, you’d create three classes:

- Player

- Enemy

- Gun

And two functions:

- Shoot (in the class gun)

- Damage (in the enemy)

Obviously this method won’t always work as nicely, and in some cases you might to revise those classes and functions later on as needed, but in 90% of the cases this skeleton is a good place to start. It basically transforms your big problem “how do I implement this feature?” to “how do fill this Shoot- and Damage-function?”.

When talking with more experienced programmers they also might raise their eyebrows about this approach, and they might start talking about the “proper” way of doing things, UML diagrams and component systems. All valid approaches, but there is a high chance your class skeleton is finished before they finished their lecture.

If in doubt: Code more

I often hear coding described as a skill that doesn’t benefit much from practice. You either know how to code feature X or you don’t. I can see where this perception comes from, after all there are certain pieces of knowledge that you just have to learn before you can even start writing your first line of code. But after those first steps, coding is absolutely a skill like any other: You have to code to get better at it, and there’s no way around it. And to do that, it helps a lot to be brave. Write things, break them, and see where and how they break. You can always revert your changes! After all, you are using version control, aren’t you? 😉

And who knows, after a few days you might even call yourself a programmer. And even if you don’t, that’s fine too. After all, even non-programmers can program.

In case you want to dive deeper in game programming, you can follow me at Mastodon, Bluesky or LinkedIn. I publish new articles about game programming, Unreal and game development in general about every month 🙂

Leave a comment