Do you feel spoiled by modern hardware? I know I do. Even the cheapest CPUs have at least 4 cores nowadays, running billions of operations per second. The idea that you could run any software on less than a GHz almost seems like fiction. Yet, there was a time when whole games ran at hardware a thousand times less powerful than that.

When thinking about impressive technical achievements in retro games, most people will first point to graphical milestones set by action games like Doom or Quake. Rightfully so, but at least I am personally far more impressed by the early examples of the city builder genre. Simulating whole economies on a large scale with a fraction of today’s power seems impossible if modern builder games even struggle on modern machines.

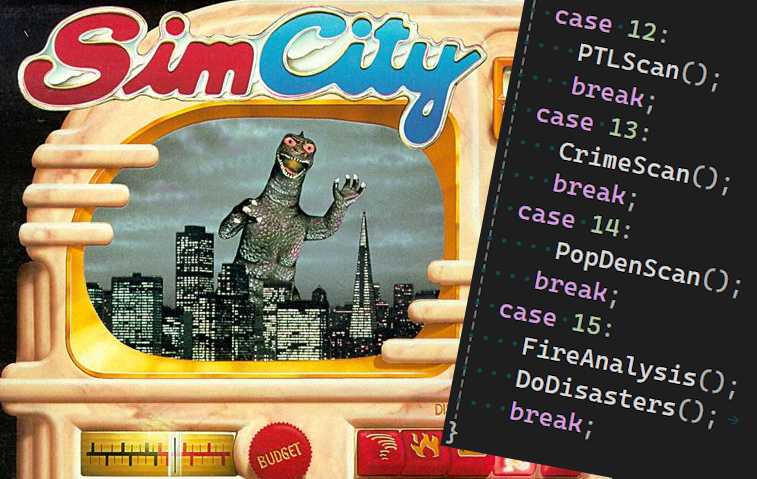

Of course this didn’t stop developers in the past to develop and run city builder games on significantly weaker hardware. The original SimCity for example lists Intel’s 386SX as the CPU in it’s system requirements. A CPU which at the time of it’s launch ran at magnificent 16 MHz.

(Note: an earlier version of this text mistakenly assumed that it ran on 12.5 MHz, which was the clock rate of base version of CPU, not the SX version. Whoops.)

The idea of running a full game, especially one in the traditionally CPU-heavy genre of city builders? Pure magic from a modern point point of view.

So, why could Maxis run a full city simulation on this ancient hardware, when nowadays even simple idle games require multiple gigahertz of CPU power?

Of course there are a lot of reason for this, most of them external (OS ecosystem etc.) but this doesn’t mean that there are no clever optimizations done in the game code itself. Luckily, this source code was made public and released under the GPL license in 2008, under the name Micropolis. Don’t be confused by the name, this is still the code of the original name, but since only the code was made open source, not the trademark, it has to be called differently. But even under a different name, this is a precious resource, since we can exactly see how the game managed to run so well.

As is often the case when analyzing software performance, we can ignore 90 percent of the code. Our focus is on the core of the city simulation, the components that update systems such as traffic, fire, power, and crime.

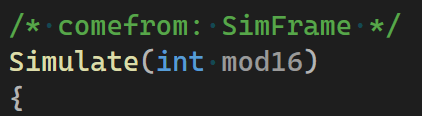

And there is indeed one single function responsible for doing all of this: The Simulate() function in s_sim.c

As the comment implies, this function is called every frame and the function itself then calls the update functions of the various game systems, like CrimeScan(), FireAnalysis(), CollectTax etc.

The catch is that calling all those functions every frame would overwhelm our poor 1989 CPU. The solution: Not calling every function every frame.

Yep, SimCity just skips most of the simulation. Did you see the mod16 parameter of the Simulate function? Where you would normally expect a deltaTime? This number loops through the numbers 0 to 15 (you probably knew this already because of the name, didn’t you?), and is then used to decided which part of the simulation is run in this specific frame. The code for this looks something like this:

(Note: This is not the exact source, I removed some stuff to make it clearer for the explanation, but it’s veery close) .

So, obviously this makes the Simulation much faster to calculate, but how does this affect the gameplay? Well in case of SimCity, I would say barely. On average the simulation of an aspect takes 8 frames to react to the player’s action, 15 frames in the worst case. As an input lag for a shooter this would be obviously a disaster, but for the simulation of a city? I’d argue it might actually feel better than an instant reaction.

So far this optimization seems very specific for one kind of type of game, but actually it is the starting point for a lot of optimizations.

Let’s look at another example, this time from Assetto Corsa (2014).

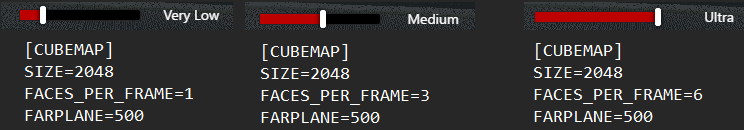

As a racing games one of it’s visual requirements is to render cars in a shiny way. To render those reflections the game uses the very common technique of regularity updated cubemaps. For a more detailed explanation what those are you can see my article on reflection rendering.

Since updating a whole cubemap every single frame would be a way to expensive task, the game uses a very similar trick as SimCity: It doesn’t update all 6 faces of the cubemap at once, but only a few, depending on the reflection quality setting.

The settings UI doesn’t say so explicitly, but looking in the .ini file, we see the effect on the variable named FACES_PER_FRAME:

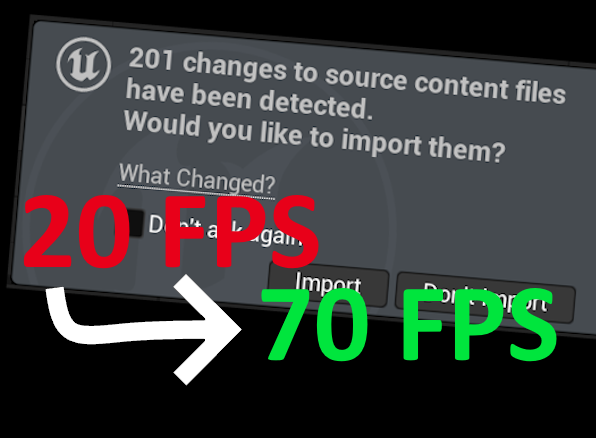

So far, we have stuck to the concept of distributing work across multiple frames by cutting longer tasks into fixed-size portions. For other tasks, it might be smarter to also determine the size and contents of those portions at runtime. For rendering tasks, this could be determined by factors such as screen size or the time since the last update. This explains why Unreal’s Lumen looks so good: It doesn’t need to recalculate all the lighting every frame. This is arguably also the reason why its results can look weird sometimes, for example, when reflections are not fully updated, like here:

Although such frame-distribution optimizations are most common in rendering code, I hope the SimCity example shows that they can work in other areas as well. The next time you work on gameplay code, ask yourself: “Do I really need to run all this code every frame?”

If you enjoyed this article consider following me at Mastodon, Bluesky or LinkedIn or subscribe to this blog directly below this article. I publish new articles about game programming, Unreal and game development roughly every month.

Leave a comment